IN THIS SECTION

Causes of the Failure

Waccamaw failed because its board of directors and senior management did not control the risks associated with its rapid growth strategy. This strategy consisted of expanding the bank's branch network and growing its commercial real estate (CRE) lending portfolio, particularly the acquisition, development, and construction (ADC) segment of the CRE portfolio. As a result of this strategy, Waccamaw developed high CRE and ADC loan concentrations. Meanwhile, the bank's branch network expansion increased overhead expenses and decreased the bank's profitability. This combination heightened Waccamaw's vulnerability to weak economic conditions. Following a decline in the bank's local economy, the CRE loans in its portfolio experienced substantial losses, which began to erode capital.

In an effort to raise capital, Waccamaw entered into an asset swap transaction. A component of this transaction involved the bank selling its noncumulative perpetual preferred stock for $16.3 million.6 FRB Richmond made a material supervisory determination that prohibited Waccamaw from considering the $16.3 million in proceeds resulting from the sale as regulatory capital because FRB Richmond considered the asset swap transaction to be a circular transaction in which the bank funded the sale of its own capital.7 In response to this material supervisory determination, Waccamaw filed a series of appeals that ultimately proceeded to the Board for consideration. In January 2012, a Board Governor reversed the results of the prior appeals and allowed Waccamaw to consider $8.4 million of the proceeds from the preferred stock sale as regulatory capital. Nevertheless, Waccamaw's persistent asset quality deterioration continued its losses, which further depleted capital and resulted in the bank becoming critically undercapitalized in April 2012. The State appointed the FDIC as receiver and closed the bank on June 8, 2012.

Management Pursued an Aggressive Growth Strategy

From 1999 through 2011, Waccamaw's total assets increased from $38 million to $566 million and the number of branch locations increased from 3 to 17. The bank's total asset growth was primarily due to its CRE lending activities, as management sought to capitalize on the burgeoning real estate development market in North Carolina's coastal areas. In its 2007 five-year strategic plan, Waccamaw's management noted its intent to (1) continue to grow to $1 billion in total assets by 2013 and (2) increase the number of branches to more than 20 by 2012. FRB Richmond examiners warned management that this expansion strategy would impact Waccamaw's capital, earnings, and liquidity. During the same examination, FRB Richmond examiners noted that Waccamaw's back-office infrastructure was "overburdened" even before management began to pursue its branch network expansion objectives outlined in the five-year plan.

CRE and ADC Concentrations Increased Exposure to Declining Economy

Since its inception, Waccamaw's core business activities included CRE lending. To increase the size of its loan portfolio, Waccamaw pursued a rapid growth strategy that focused on CRE lending. Initially, the bank funded its CRE lending growth by using core deposits. Beginning in 2007, management transitioned to brokered deposits as a funding source to accelerate growth. We noted that from 2002 through 2009, Waccamaw's reliance on brokered deposits as a funding source increased from $7 million to $125 million. According to the CBEM, brokered deposits can weaken a bank by allowing it to grow too quickly. Additionally, reliance on noncore funding is risky because such funding may not be available in times of financial stress or adverse changes in market conditions.

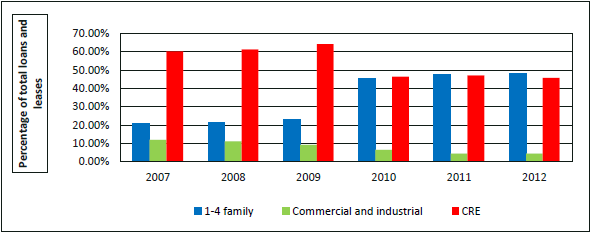

From 2002 through 2008, Waccamaw's CRE loan portfolio grew 650 percent, from $31.6 million to $237 million. Further, ADC loans, a component of the CRE portfolio, increased 431 percent, from $23.7 million to $125.9 million. As illustrated in figure 1, CRE loans were more than 50 percent of the bank's loan portfolio until 2009. Waccamaw's rapid loan growth led to high CRE and ADC loan concentrations. These loan concentrations heightened Waccamaw's exposure to downturns in its local markets.

Figure 1: Waccamaw's Loan Types as Percentage of Total Loans and Leases, 2007–March 2012

Source: Waccamaw's Call Reports, December 2007 through March 2012.

Notes: Data for 2007–2011 are year-end; data for 2012 are through March. The label 1–4 family refers to loans secured by single-family properties. Some of these loans include single-family home mortgages and home equity lines of credit.

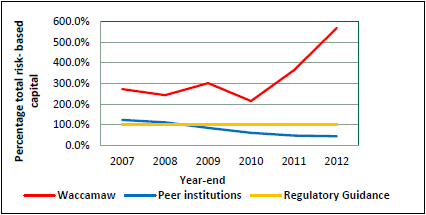

Figure 2 illustrates Waccamaw's ADC concentration from December 2007 to March 2012. The bank's ADC concentration was more than twice the threshold outlined in the Board's Supervision and Regulation Letter 07-1, Concentrations in Commercial Real Estate Lending, Sound Risk Management Practices (SR Letter 07-1), for an institution presenting a potentially significant ADC concentration risk.8 Conversely, from 2007 to 2012, Waccamaw's peer institutions decreased their ADC concentration levels from 123.6 percent of total risk-based capital to 44.2 percent. ADC concentrations generally present heightened risk because a developer's capacity to repay a loan depends on whether the developer can obtain long-term financing or find a buyer for the completed project.

Figure 2: ADC Concentrations, 2007–March 2012

Source: Waccamaw's Uniform Bank Performance Reports, December 2007 through March 2012.

Note: Data for 2007–2011 are year-end; data for 2012 are through March.

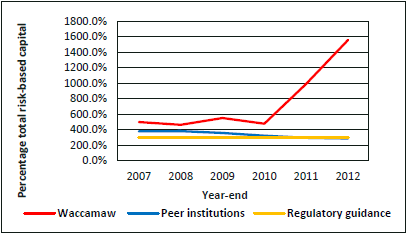

Figure 3 illustrates Waccamaw's CRE concentration as a percentage of total risk-based capital from December 2007 to March 2012. During this time period, the bank also exceeded (1) the threshold in SR Letter 07-1 for an institution presenting a potentially significant CRE concentration risk and (2) its peer institutions' CRE concentration levels. As highlighted in our September 2011 Summary Analysis of Failed Bank Reviews, asset concentrations tied to CRE loans increase a bank's vulnerability to changes in the marketplace and compound the risks inherent in individual loans.

Figure 3: CRE Concentrations, 2007–March 2012

Source: Waccamaw's Uniform Bank Performance Reports, December 2007 through March 2012.

Note: Data for 2007–2011 are year-end; data for 2012 are through March.

Branch Expansion Affected Profitability

In 2007, management began implementing its growth strategy by expanding its branch network, even though FRB Richmond examiners expressed concerns regarding management's decision to open additional branches. The bank opened 6 branches in 2007. As part of Waccamaw's 2007 five-year strategic plan, the bank anticipated opening 2 or 3 branches every year until it had a total of 25 branches. Waccamaw's total assets and deposits increased after the new branches became operational. From 2007 through 2008, Waccamaw's total assets increased 6 percent, or by $29.3 million. In addition, the bank's core deposits increased 11.6 percent while brokered deposits increased 439.7 percent.

From December 2007 through December 2008, the bank's noninterest expense increased 51 percent, from $12.3 million to $18.5 million. In 2009, State examiners reported that Waccamaw's overhead expenses had increased by $4.8 million due to the addition of new branches. During the same examination, State examiners noted that the six branches opened in 2007 had yet to be profitable. Further, Waccamaw's net interest margin,9 an indicator of the bank's profitability, became strained due to its declining interest income and high cost of funds associated with the use of brokered deposits. During 2007 and 2008, Waccamaw's net interest margin declined by 114 basis points, while its peer institutions' net interest margin declined by 24 basis points.10

Corporate Governance Weaknesses and Management Failures Led to Enforcement Actions

Waccamaw's management implemented an aggressive growth strategy that relied on CRE lending funded by brokered deposits. However, management failed to implement adequate risk management practices and effective controls to monitor the bank's increasing risk, particularly in its CRE portfolio. Specifically, Waccamaw's management failed to implement examiner recommendations designed to improve the bank's credit risk management. During a February 2009 examination, examiners recommended that the bank (1) maintain a loan review system that could assist with managing risk in the loan portfolio, (2) ensure that loan reviews include appropriate documentation, and (3) enhance reporting on loan portfolio stratification. These recommendations were recurring findings highlighted during previous examinations. As a result of management's inability to adequately address these recommendations, FRB Richmond implemented successive enforcement actions, including a board resolution in July 2009 and a written agreement in June 2010.

Among other things, the board resolution compelled management to perform a comprehensive review of credit administration, loan review, and risk grading. The written agreement, among other things, required management to submit a capital plan and perform a management assessment. In addition, the enforcement action prohibited the bank from (1) declaring or paying any dividends without prior regulatory approval or (2) accepting or renewing any brokered deposits.

The results of the management assessment performed by a third party revealed that Waccamaw's board emphasized profitability and growth over strong risk management. In addition, the management assessment report noted that management did not adapt to declines in the local real estate market. Further, the report mentioned a disagreement between board members concerning the need to raise capital. According to the report, the bank's former Chairman and a specific board member sought to prevent any shareholder dilution and concerns about shareholder dilution took precedence over the bank's deteriorating condition. One board member resigned because of the disagreement concerning the need to raise capital. The report recommended that Waccamaw add a skilled Chief Financial Officer, remove three board members, and supplement the board's knowledge by using consultants.

Decline in Local Economy and Asset Quality Deterioration Resulted in Losses

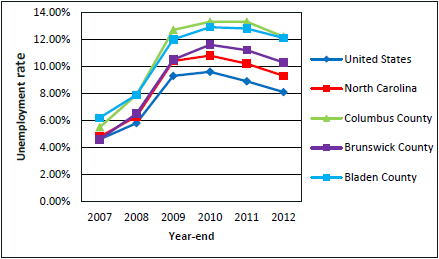

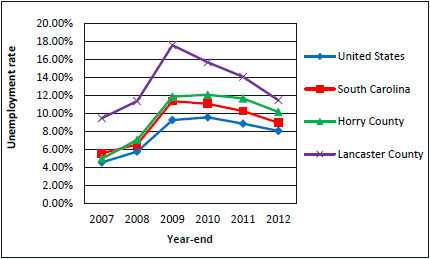

Beginning in 2007, examiners identified a decline in Waccamaw's local economy, particularly in the local real estate market. From 2007 through 2011, the bank's delinquent ADC loans increased from $85,000 to $10.2 million. Examiners advised management to strengthen its use of economic data so that it could adapt to changing local market conditions. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the growing unemployment rate in the bank's local markets. Those markets experienced higher unemployment rates than the respective states and the national averages. Waccamaw could not adapt to these declines because of its high concentration levels and limited options for raising deposits.

Figure 4: North Carolina Unemployment, 2007–2012

Source: FDIC Regional Economics Condition website.

Note: Columbus, Brunswick, and Bladen Counties are those in which Waccamaw had branch locations.

Figure 5: South Carolina Unemployment, 2007–2012

Source: FDIC Regional Economics Condition website.

Note: Horry and Lancaster Counties are those in which Waccamaw had branch locations.

As the bank's local economy declined, noncurrent and nonaccrual loans increased. From 2007 through 2012, Waccamaw's total nonaccrual loans increased from $4 million to $41 million. In 2009, examiners reported that a majority of the nonaccrual loans were ADC loans. Further, from 2007 through March 2012, Waccamaw's foreclosure losses and other-real-estate-owned losses increased from $0 to $14.7 million and from $318,000 to $9.7 million, respectively.

Deficient Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses Level and Methodology Limited Management's Ability to Forecast Losses

Examiners repeatedly criticized Waccamaw's allowance for loan and lease losses methodology. For instance, in 2010, FRB Richmond examiners highlighted the divergence between the bank's allowance for loan and lease losses methodology and current accounting or regulatory practices. During the March 2011 State examination, examiners noted that the bank's methodology did not incorporate an analysis of the $110 million home equity line of credit (HELOC) portfolio the bank purchased in December 2010.

Because the bank's management lacked the tools to adequately manage its CRE portfolio, Waccamaw could not effectively forecast the reserves needed to offset anticipated loan and lease losses. Therefore, as loan losses increased, the bank's provision expenses increased to address the deficiencies in the allowance for loan and lease losses, which further strained profitability.

Capital Erosion and Effort to Raise Capital Led to Acquisition of HELOC Portfolio

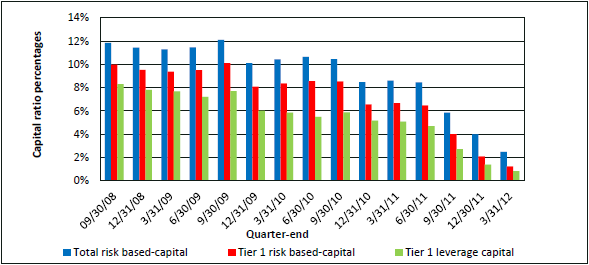

Figure 6 illustrates that Waccamaw remained well capitalized until December 2010.11 Nevertheless, examiners noted as early as August 2009 that current capital levels could not support the bank's risk profile. Asset quality deterioration in the CRE portfolio and provision expenses impacted earnings. Waccamaw took provision expenses of $2.9 million in 2008 and $16.6 million in 2009. Increasing provision expenses eliminated earnings and began to erode the bank's capital. As a result, the 2010 written agreement required management to recapitalize the bank. Waccamaw submitted the first of several capital plans in October 2010.

Figure 6: Waccamaw's Quarterly Capital Ratios, September 30, 2008–March 31, 2012

Source: Waccamaw's Quarterly Uniform Bank Performance Reports, September 2008 through March 2012.

Asset Swap Transaction Failed to Improve the Bank's Condition

In August 2010, Waccamaw's management met with FRB Richmond and State examiners to discuss alternatives for raising capital. Management outlined several options, including (1) the sale and leaseback of assets and (2) an asset swap involving nonperforming assets for first mortgage loans or HELOCs. On December 22, 2010, Waccamaw completed an asset swap transaction in which the bank purchased a $110 million HELOC portfolio for $99.3 million cash and $11.2 million in nonperforming asset loans. The following day, the bank completed another transaction in which it received $16.3 million from the sale of its noncumulative perpetual preferred stock.

FRB Richmond examiners highlighted several concerns about the asset swap transaction: (1) the price of the HELOC portfolio, (2) the relationship between parties in the transaction and the source of the funds used to complete the $16.3 million preferred stock purchase, and (3) the effectiveness of the credit enhancement provided by the seller of the HELOC portfolio.

Due, in part, to the asset swap transaction occurring the day before the preferred stock sale, FRB Richmond examiners suspected that proceeds associated with the asset swap transaction funded the preferred stock purchase. In an e-mail to bank management, an FRB Richmond official reported that Waccamaw wired the funds for the HELOC portfolio on December 22, 2010, and the bank received $16.3 million for payment of its preferred stock on December 23, 2010. The same FRB Richmond official noted that the counterparties in the asset swap transaction and the preferred stock purchase had not provided certified financial statements. This omission increased FRB Richmond's suspicions that the preferred stock sale could not have occurred without the asset swap transaction. Based on these findings, FRB Richmond prohibited Waccamaw from considering the $16.3 million as regulatory capital in June 2011. As a result, Waccamaw filed a series of appeals—to FRB Richmond's appeals panel on September 8, 2011; to the President of FRB Richmond on November 1, 2011; and to the Board on December 20, 2011.

The material supervisory determination prohibiting Waccamaw from considering the proceeds associated with the preferred stock sale as regulatory capital required Waccamaw to refile its March 2011 Call Report. The revised filing lowered the bank's PCA status from well capitalized to undercapitalized.12 Due to an ongoing decline to its capital resulting from continued CRE loan losses, examiners asked Waccamaw to submit a capital restoration plan by August 2011. Waccamaw submitted two capital restoration plans, in September 2011 and in October 2011. Examiners rejected both plans due to a lack of firm commitments from investors and management's unrealistic and inaccurate assumptions supporting the accompanying financial projections. Waccamaw became critically undercapitalized in September 2011.

Because of the continued capital erosion, FRB Richmond issued a PCA notice in December 2011. The PCA notice directed management to restore the bank to adequately capitalized status by January 2012. The Board's appeal decision permitted the bank to consider $8.4 million of the $16.3 million from the sale of the preferred stock as regulatory capital, Waccamaw's PCA status improved to significantly undercapitalized as of January 2012. However, continued asset quality deterioration in the bank's loan portfolio and the resulting losses caused Waccamaw to become critically undercapitalized as of April 9, 2012.13 As a result, the State appointed the FDIC as receiver.

- 6. Noncumulative perpetual preferred stock allows the issuer to waive payment of dividends. Dividends do not accumulate to future periods nor do they represent a contingent claim on the issuer. Return to text

- 7. Title 12, Code of Federal Regulations, part 225, appendix A, section II(i), states that to qualify as an element of tier 1 or tier 2 capital, an instrument must be fully paid up and effectively unsecured. Accordingly, if a banking organization has purchased, or has directly or indirectly funded the purchase of, its own capital instrument, that instrument generally is disqualified from inclusion in regulatory capital. Return to text

- 8. According to SR Letter 07-1, an institution presents a potentially significant CRE concentration risk if total reported construction, land, and development loans represent 100 percent or more of its total capital. Return to text

- 9. Net interest margin is a performance metric used to evaluate a bank's profitability by measuring the difference between interest income generated in comparison to the interest paid. Return to text

- 10. A basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point. Return to text

- 11. Although Waccamaw was well capitalized as of December 2010, an FRB Richmond July 2011 directive required the bank to refile its December 2010 and March 2011 Call Reports. The refilings accelerated the decline in the bank's PCA status from well capitalized in December 2010 to undercapitalized as of March 2011. Return to text

- 12. Per the CBEM, PCA uses the total risk-based capital, tier 1 risk-based capital, and tangible equity ratio for assigning state member banks to one of the five capital categories (well capitalized, adequately capitalized, undercapitalized, significantly undercapitalized, and critically undercapitalized). A bank is considered undercapitalized if the total risk-based ratio is less than 8 percent, the tier 1 risk-based capital and leverage ratio is less than 4 percent, or the leverage ratio is less than 3 percent and the bank received a CAMELS composite rating of 1 in its most recent examination and is not experiencing or anticipating any growth. Return to text

- 13. Once a bank becomes critically undercapitalized under PCA standards, the bank has a 90-day window to improve its condition; otherwise, it is closed by the applicable chartering authority with the concurrence of the FDIC. Return to text