IN THIS SECTION

Board Report: 2013-IE-B-002 March 22, 2013

Review of the Failure of Bank of Whitman

available formats

-

Executive Summary:

PDF | HTML -

Full Report:

PDF (2 MB) | HTML - Accessible version

Causes of the Failure

Whitman failed because of the convergence of several factors. The bank altered its traditional agricultural lending strategy and expanded into new market areas, which resulted in rapid growth and high CRE concentrations as well as credit concentrations to individual borrowers. Whitman's corporate governance weaknesses allowed the bank's senior management to dominate the institution's affairs and undermine the effectiveness of key control functions. Whitman's credit concentrations and poor credit risk management practices, along with a decline in the local real estate market, resulted in asset quality deterioration and significant losses. At that point, management engaged in a series of questionable practices to mask the bank's true condition. The escalating losses depleted earnings, eroded capital, and left the bank in a PCA critically undercapitalized condition, which prompted the State to close Whitman and appoint the FDIC as receiver on August 5, 2011.

Loan Concentrations

For nearly 30 years, Whitman's traditional business activities focused on agricultural lending, its management team's area of expertise. Prior to converting to state member bank status, Whitman altered its strategy to focus on CRE lending as part of its growth efforts. However, according to an FRB San Francisco interviewee, the board of directors and management lacked adequate commercial lending experience. Whitman's outside directors included farmers, an attorney, a retired banker, and a physician. The retired banker was the only outside director with prior banking experience.

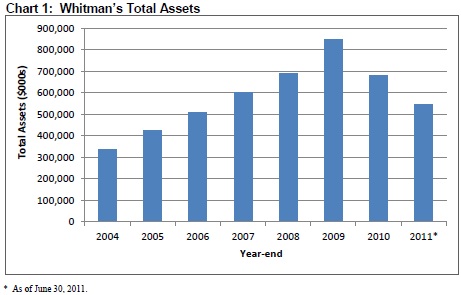

As shown in chart 1, the bank's pursuit of a rapid growth strategy resulted in its total assets increasing more than 150 percent, from approximately $335 million in 2004 to approximately $847 million in 2009. As part of its growth strategy, Whitman expanded into new geographic areas and diversified its lending activities. Whitman expanded into Spokane, Washington, which FRB San Francisco examiners described as a saturated and highly competitive market. Whitman also experienced significant growth in its CRE lending activities, eventually resulting in high CRE concentrations. As highlighted in our September 2011 Summary Analysis of Failed Bank Reviews, 4 asset concentrations tied to CRE or construction, land, and land development loans increase banks' vulnerability to changes in the marketplace and compound the risks inherent in individual loans.

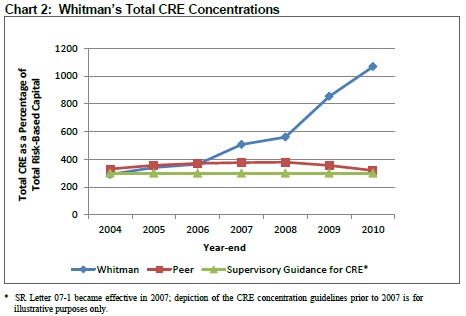

As illustrated in chart 2, Whitman's CRE concentration increased from approximately 292 percent of total risk-based capital in December 2004 to approximately 854 percent in December 2009. Whitman's CRE loans as a percentage of total risk-based capital significantly exceeded both the supervisory criteria for concentration risk noted in the Federal Reserve Board's Supervision and Regulation (SR) Letter 07-1, Concentrations in Commercial Real Estate Lending, Sound Risk Management Practices, and the levels of its peers.5

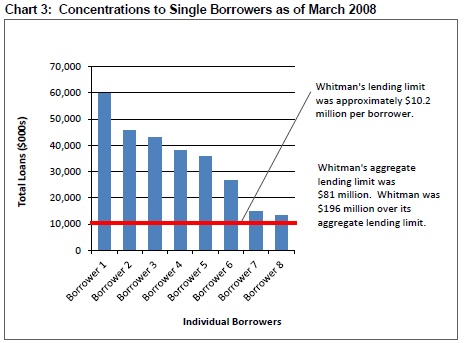

In addition to significant CRE concentrations, in 2007 FRB San Francisco identified that Whitman had high loan concentrations to individual borrowers. These concentrations increased the risk that a single borrower experiencing financial difficulties could substantially diminish the bank's capital position. In 2008, the violations of laws and regulations section of the State's examination report noted the bank's legal lending limit violations related to eight individual borrowers.6 During the 2008 examination, Whitman's legal lending limit to an individual borrower was approximately $10.2 million. The loans for these eight borrowers totaled approximately $277 million and exceeded the aggregate lending limit for these borrowers by $196 million (chart 3). Loans to one of the eight borrowers, an individual ultimately subject to Securities and Exchange Commission charges for engaging in securities fraud and operating a Ponzi scheme,7 totaled approximately $60 million and accounted for 118 percent of the bank's capital.8 In 2009, FRB San Francisco stated that the concentrated lending to this one borrower was the root cause for 38 percent of the bank's classified loans. This relationship ultimately resulted in significant losses. As of 2011, Whitman's management had done little to correct these violations or to mitigate the risks associated with these concentrations of credit.

In our opinion, Whitman's pursuit of a rapid growth strategy coupled with the lack of adequate CRE lending experience of its board of directors and management resulted in CRE and individual borrower concentrations that presented heightened risk to the institution.

Corporate Governance Weaknesses

FRB San Francisco and State examiners identified a number of corporate governance weaknesses at Whitman. These weaknesses included dominant management,9 conflicts of interest and nepotism that undermined the effectiveness of key control functions, a deficient board of directors and senior management team, and a weak internal audit function.

Dominant Management

Whitman's president, chief executive officer (CEO), and chairman of the board (hereafter referred to as the CEO) controlled the institution's strategy. In every full-scope examination report from 2005 to 2011, FRB San Francisco examiners noted the CEO's dominance. Furthermore, during interviews, several FRB San Francisco and State examination staff members commented that Whitman's management team did not embrace constructive criticism during the examination process. FRB San Francisco examiners also mentioned that several outside directors appeared to have a prior personal or professional relationship with the CEO. We believe that these apparent connections allowed the CEO to maintain his dominance. In 2010, the State issued a Consent Order that required Whitman's board of directors to engage an independent assessment of the bank's management. Whitman's independent directors retained an external firm to conduct the assessment, which included employee interviews and questionnaires. Many employees interviewed by the external firm noted their unwillingness to communicate concerns to the CEO regarding issues impacting the bank because they feared retaliation.

Whitman's chief lending officer (CLO) and chief financial officer (CFO), who were members of the board of directors, also exerted dominance over Whitman throughout much of the bank's history. In its management assessment, the external firm concluded that the CEO, CLO, and CFO were involved in virtually all of the institution's decisions.

Conflicts of Interest and Nepotism

During the five years prior to Whitman's closure, senior management hired relatives as potential successors to management in a manner that compromised the independence of key control functions and created conflicts of interest. An external firm's management assessment revealed several family relationships tied to the CEO, CLO, and CFO. This assessment noted that the nepotism at Whitman added strain to an already weak management system.

According to an FRB San Francisco interviewee, it is common for small community banks to employ family members. While federal banking statutes and regulations do not explicitly prohibit nepotism in small community banks' employment practices, the CBEM states that offices staffed by members of the same family require special alertness on the part of the examiner. In our opinion, the extensive nepotism at Whitman created conflicts of interest and compromised several key control functions. For example, the CEO's daughter held conflicting positions at Whitman. She served as the compliance officer while also serving as a loan officer with her own loan portfolio. In our opinion, serving as a loan officer impaired her ability to objectively review her loan portfolio for potential compliance violations in her role as the compliance officer. We believe that her conflicting responsibilities evidenced multiple internal control weaknesses, including a failure to appropriately segregate duties. FRB San Francisco raised concerns about this arrangement with Whitman management, noting that it presented a conflict of interest and independence issues. Also, we believe that the familial relationship between the CEO and his daughter compromised the independence of the compliance function.

As another example, the CLO's son served as the chief internal auditor. According to SR Letter 03-05, Interagency Policy Statement on the Internal Audit Function and its Outsourcing, the internal audit function's role should be to independently and objectively evaluate and report on the effectiveness of an institution's risk management, control, and governance processes. The relationship between the CLO and the chief internal auditor presented a conflict of interest that impaired the independence of Whitman's internal audit function.

Deficient Board of Directors and Senior Management

Whitman's board of directors and senior management established the institution's strategic focus on CRE and developing large lending relationships with individual borrowers. The board of directors and senior management failed to develop a risk management system commensurate with the risk associated with these activities.10 In addition, the board of directors failed to take action when presented with information detailing questionable practices and improper conduct involving senior management.

FRB San Francisco and State examiners consistently noted deficiencies in the bank's risk management practices and in the board of directors' and management's oversight. As a result of a 2005 examination, FRB San Francisco issued a commitment letter to address Whitman's risk management weaknesses. In 2007, FRB San Francisco found Whitman to be in compliance with the commitment letter and terminated the action, but noted that the recently implemented risk management processes required validation to ensure their effectiveness. While the board of directors and management took some steps to address the deficiencies, they did not maintain effective risk management practices or improve their oversight. In subsequent examinations, FRB San Francisco and State examiners continued to identify risk management weaknesses, including unsecured lending and the need to strengthen credit administration and underwriting practices. Despite these recurring issues, examiners did not downgrade Whitman's management component rating until September 2009. In July 2010, examiners implemented a formal enforcement action, which required the board of directors to strengthen its oversight of Whitman's management and operations. However, the weaknesses remained unresolved.

Dominant members of management often ignored internal controls and did not always report deviations from policy to the board of directors. The board of directors failed to take action when presented with forensic accounting reports and employee letters detailing questionable practices and improper conduct involving senior management. One forensic accounting report, issued in December 2010, notified the board of directors of a transaction involving material departures from prudent banking practices and the bank's own written policies. This forensic accounting report detailed inappropriate conduct by senior officers to conceal two long-standing delinquent loans. Another forensic accounting report, also issued in December 2010, notified the board of directors of a transaction involving inappropriate conduct by senior bank officers in relation to the sale of other real estate owned (OREO); the report concluded that the transaction was "ill-conceived." In addition, in a March 2011 letter, several employees notified the board of directors that Whitman's senior management allegedly coerced Whitman employees into obtaining personal loans to purchase Whitman stock. The board of directors failed to take action to address these issues and failed to notify the appropriate authorities.

Weak Internal Audit

Deficiencies in Whitman's internal audit program further contributed to the overall corporate governance weaknesses. As early as 2005, FRB San Francisco examiners criticized Whitman's internal audit program and noted that the board of directors should improve the internal audit program to reflect the risk and complexity of the bank's size, structure, and processes. SR Letter 03-05 notes that the internal audit manager should ideally report directly and solely to the audit committee regarding both audit issues and administrative matters.11 In 2006, State examiners raised concerns about the independence of the internal audit function because the CLO's son served as the chief internal auditor. Furthermore, the State expressed concerns regarding the "involvement of the Chief Operating Officer in overseeing some of the internal audit activities." As a result of this examination, the State informed the board of directors that it must correct the structure of the internal audit program, as it lacked independence. Whitman responded to the criticism by outsourcing internal audit in mid-2006. During a 2008 examination, the State noted that Whitman had added a new internal auditor and adequately addressed criticisms from the previous examination.

In 2009, the audit committee's three outside directors expressed concerns regarding the number of inside directors and the difficulties of implementing change at the bank. Throughout various examinations, examiners noted other weaknesses in Whitman's internal audit program. In 2010, FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that management should improve the audit program by including a loan operations audit and increasing the frequency of key audits. In 2011, FRB San Francisco and State examiners determined that management suspended the bank's audit program, canceling various internal and external reviews, and noted that Whitman lacked an internal auditor and did not have plans to hire one in the foreseeable future.

Inadequate Credit Risk Management

Whitman's board of directors and management failed to establish a credit risk management framework and infrastructure commensurate with the risks in the bank's loan portfolio. According to the CBEM, the bank's board of directors and senior management have an important role in ensuring the adequate development, execution, maintenance, and compliance monitoring of the bank's internal controls. The CBEM notes that a component of internal control is risk assessment, which is the identification, analysis, and management of risks. FRB San Francisco noted Whitman's inadequate credit risk management during its initial examination of Whitman in 2005. During this examination, FRB San Francisco examiners identified deficiencies in credit administration and internal controls, specifically deficient underwriting; weak problem loan identification; inadequate credit risk identification; lack of an independent credit review process; and several weaknesses in the appraisal process, including dated or inadequately supported appraisals and the failure to obtain appraisals. As noted previously, upon conclusion of this examination, FRB San Francisco and Whitman entered into a commitment letter to address the bank's risk management weaknesses. FRB San Francisco terminated the action in 2007 but noted that the recently implemented risk management processes had not yet been tested or validated.

In subsequent years, the bank made little progress toward developing credit administration practices consistent with the heightened risk in the loan portfolio. During this period, examiners identified a number of weaknesses in Whitman's credit risk management practices, including the following:

- liberal and lax underwriting, including failure to cite exceptions to policy, inadequate cash flow or global debt analysis for significant relationships, and poor guidance for underwriting CRE loans

- inadequate monitoring related to credit concentrations

- unreliable and deficient problem loan recognition, including inaccuracies in loan grading and delays in downgrading loan risk grading based on deteriorating loan performance

- deficiencies in the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL) methodology

- widespread repeat federal regulatory and state legal lending limit violations, such as violations of subpart G of Regulation Y, Bank Holding Companies and Change in Bank Control, for various deficiencies in appraisal practices12

Whitman's credit risk management weaknesses continued and remained unresolved through the bank's failure.

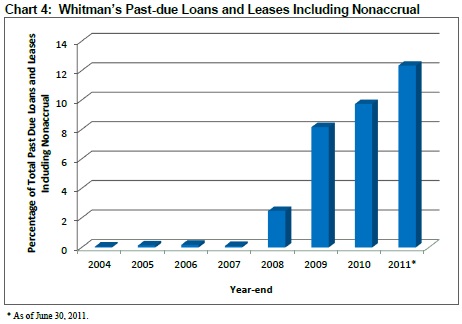

Deterioration in Asset Quality

As a result of Whitman's concentrated lending, Whitman's inadequate credit risk management framework, and a declining local real estate market, the bank's classified assets steadily increased and asset quality deteriorated. As illustrated in chart 4, Whitman's past-due loans and leases began to increase dramatically in 2008. In addition, adversely classified assets grew by more than $90 million from a 2009 full-scope examination to a 2010 full-scope examination and represented approximately 339 percent of tier 1 capital and the ALLL by 2011.

FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that many factors contributed to the deterioration of Whitman's asset quality. These factors included liberal underwriting, borrower and CRE concentrations, poor selection of risk, and the untimely identification of credit risk. As a result of these weaknesses, Whitman was extremely vulnerable to a softening real estate market. An FRB San Francisco examiner stated that the economic downturn did affect Washington State. As the real estate market began to deteriorate, Whitman became overwhelmed as its customers struggled to make loan payments, which adversely impacted asset quality. In a September 2009 examination, FRB San Francisco identified the economic downturn as a significant factor in Whitman's decline in asset quality. Furthermore, FRB San Francisco examiners noted that management's attempt to aggressively resolve problem loans resulted in an increase in liberal underwriting through unsecured lending, which contributed to the deterioration of Whitman's asset quality.

Questionable Transactions and Business Practices

As Whitman's asset quality deteriorated, its senior management used various measures to conceal the extent of problem loans and mask the bank's true condition. These measures included questionable transactions involving a bank-approved appraiser as well as a strategy of replacing secured problem loans with new unsecured loans that had questionable structures and liberal underwriting. These actions caused the bank to suffer further losses. In addition, a letter from several Whitman employees alleged that senior management coerced them into obtaining personal loans to purchase Whitman stock in an attempt to bolster the bank's capital.

Questionable Transactions Involving a Bank-approved Appraiser

In 2010, FRB San Francisco noted that a bank-approved appraiser's son obtained a loan from Whitman for "business purposes or business investments." FRB San Francisco and State examiners identified that the appraiser's son instead used the proceeds to make outstanding interest payments on a loan that his father had obtained from the bank. Examiners described this arrangement as a diversion of loan funds involving a "straw borrower" and directed management to notify the appropriate authorities regarding this transaction. Management filed notification forms regarding this transaction and FRB San Francisco subsequently filed its own notification forms related to the same transaction.

FRB San Francisco, the State, and an external firm criticized another transaction involving the same appraiser. Whitman extended a loan to a limited liability company to facilitate the sale of OREO property. The appraiser had an ownership interest in the limited liability company and served as guarantor for the loan. The bank initially used a 2008 appraisal that this guarantor performed on the property. Examiners noted that this arrangement had the appearance of self-dealing and posed a potential conflict of interest. An external firm concluded that the purpose of the transaction was to eliminate the negative effects of a bad commercial loan on Whitman's books. The firm concluded that the transaction was "ill-conceived" and "not at arms-length." FRB San Francisco filed the appropriate notification forms regarding this transaction.

Unsecured Lending

In addition, Whitman's management increasingly engaged in unsecured lending by replacing secured problem loans with new unsecured loans to conceal the bank's true condition. FRB San Francisco and State examiners identified that this strategy frequently involved selling a troubled note or a 100 percent participation in the troubled note to a new borrower. Whitman would finance this arrangement by extending an unsecured loan to the new borrower and only requiring interest or principal payments at maturity, often at a concessionary low rate. The CBEM states that an unsecured loan portfolio can represent a bank's most significant risk and that if a borrower's financial condition deteriorates, the lender's options to resolve the lending relationship deteriorate as well.

As early as 2006, Whitman engaged in unsecured lending. In 2008, State examiners identified that the bank had several large borrowers with unsecured lines of credit and instructed Whitman to enhance its unsecured lending guidelines. During full-scope and target examinations in 2009, FRB San Francisco examiners issued a Matter Requiring Immediate Attention instructing the board of directors to improve its monitoring of unsecured lines of credit.13 Whitman's management did not establish a limit on the amount of unsecured loans in the portfolio. As of year-end 2009, outstanding unsecured loans totaled $106 million, or 17 percent of the loan portfolio. FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that this amount of unsecured loans elevated the risk of loss to the institution.

In 2010, FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that (1) the risks associated with Whitman's large unsecured loan portfolio were not commensurate with the current capital levels and (2) management had been instructed to develop underwriting guidelines for unsecured lending since the March 2008 State examination. Whitman, however, failed to establish underwriting guidelines for unsecured lending, which reflected unsafe and unsound credit underwriting. In 2010, examiners notified Whitman management that its strategy to minimize problem loans by liberally underwriting unsecured loans exposed the bank to additional risk. Also in 2010, an external firm reviewed a transaction involving unsecured lending and noted that its purpose was to "remove from the bank's books or camouflage" two long-standing delinquent loans. The firm concluded that this transaction involved material departures from prudent banking practices and Whitman's policies. FRB San Francisco filed the appropriate notification forms regarding this transaction.

Alleged Coercion behind Employee Stock Purchases

Whitman's senior management allegedly coerced Whitman employees into obtaining personal loans to purchase Whitman stock in an attempt to bolster the bank's capital. In March 2011, several Whitman employees claimed that they were instructed to purchase Whitman stock as a condition of their employment. They alleged that senior management informed them that loan arrangements were being made with another bank to accomplish the stock purchases. During an interview, an FRB San Francisco examiner noted that senior management provided employees with completed loan applications to sign to request these loans. The May 2011 examination report noted that directors and bank officers received Whitman lines of credit to facilitate the stock purchases. FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that this appeared to be a violation of 12 U.S.C. 324, which prohibits banks from lending on or purchasing their own stock. FRB San Francisco filed the appropriate notification forms regarding this transaction.

Deficient ALLL Level and Methodology

From 2005 to 2011, examiners repeatedly criticized Whitman's ALLL methodology. In 2005, FRB San Francisco examiners noted that Whitman's ALLL methodology was outdated. During a January 2007 examination, FRB San Francisco examiners noted that the ALLL methodology was inconsistent with regulatory guidance and generally accepted accounting principles.14From 2009 to 2011, examiners described the ALLL methodology as materially flawed, in contravention of interagency guidance, unacceptable, and needing improvement.

Additionally, as early as 2007, examiners noted deficiencies in Whitman's ALLL levels. In 2009, FRB San Francisco examiners notified Whitman that it needed an additional provision of $7 million to raise the ALLL to a minimally acceptable level. In 2010, management underfunded the ALLL by $10 million due to ineffective loan grading and a large volume of examiner downgrades. After a provision of approximately $10.6 million to bring the ALLL to $30 million at June 30, 2011, the bank fell to the PCA critically undercapitalized category.

Depleted Earnings

The deterioration of Whitman's asset quality coupled with high ALLL provisions eventually resulted in depleted earnings. In 2007, Whitman's earnings performance declined primarily due to a large loan loss in the fourth quarter of 2006; however, FRB San Francisco examiners concluded that earnings still augmented capital. Examiners labeled earnings satisfactory and sufficient in 2008 and February 2009, respectively. In September 2009, however, FRB San Francisco examiners noted that earnings were critically deficient due to high ALLL provisions and a contracting net interest margin. FRB San Francisco concluded that Whitman's earnings did not support the bank's operations, augment capital, and fund the ALLL. FRB San Francisco examiners noted that poor asset quality and weak credit risk management elevated the risk to the bank's earnings. Whitman's earnings remained critically deficient and unable to support capital through the bank's closure. In 2011, FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that additional provision expenses, further compression of the net interest margin, and high overhead costs had negatively impacted earnings.

Erosion of Capital

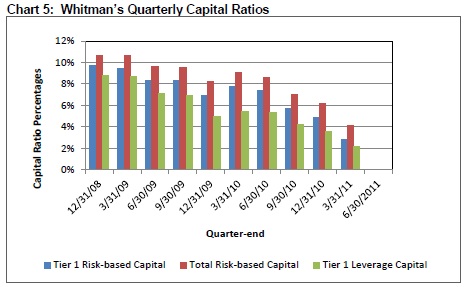

Chart 5 illustrates Whitman's quarterly capital ratios from the fourth quarter of 2008 through the second quarter of 2011. As of December 31, 2008, Whitman's tier 1 risk-based capital, total risk-based capital, and tier 1 leverage capital ratios were 9.71 percent, 10.69 percent, and 8.82 percent, respectively. FRB San Francisco examiners warned Whitman that although these capital ratios appeared adequate and met the PCA well capitalized guidelines, continued deterioration in its loan portfolio could seriously affect the bank's capital position.

During a September 2009 target examination, FRB San Francisco examiners deemed Whitman's capital inadequate for its risk profile and urged management to develop a formal capital plan to preserve and augment capital. Furthermore, Whitman could no longer rely on its holding company for capital support because the holding company was also experiencing financial strain. As of a September 2010 target examination, Whitman still had not submitted an acceptable capital plan. FRB San Francisco and State examiners noted that they had repeatedly raised this issue to the board of directors throughout the year, yet the board of directors did not exhibit any sense of urgency to aggressively raise capital. Whitman's severe asset quality deterioration continued to result in net losses and capital depletion, which caused the bank to fall to undercapitalized in the quarter ending September 30, 2010.

FRB San Francisco required Whitman to submit an acceptable capital restoration plan by November 24, 2010. Whitman failed to do so, and as a result, the Federal Reserve Board issued a PCA directive effective February 9, 2011. Whitman fell to PCA significantly undercapitalized status in March 2011 and to critically undercapitalized upon conclusion of the May 2011 examination when FRB San Francisco and State examiners required a provision of approximately $10.6 million to the ALLL. On August 5, 2011, the State closed Whitman and appointed the FDIC as receiver.

- 4. This report can be found at http://oig.federalreserve.gov/reports/Cross_Cutting_Final_Report_9-30-11.pdf. Return to text

- 5. According to the Federal Reserve Board's SR Letter 07-1, an institution presents potential significant CRE concentration risk if it meets the following criteria: (1) total reported construction, land, and development loans represent 100 percent or more of an institution's total capital or (2) total CRE loans represent 300 percent or more of the institution's total capital and the outstanding balance of the institution's CRE loan portfolio has increased by 50 percent or more during the prior 36 months. Return to text

- 6. With certain exceptions, section 30.04.111 of the Revised Code of Washington limits the total loans and extensions of credit to a borrower at any one time to 20 percent of the bank's capital and surplus. Return to text

- 7. A Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud that involves the payment of purported returns to existing investors from funds contributed by new investors. Return to text

- 8. On March 2, 2009, the Securities and Exchange Commission filed a complaint alleging that this individual engaged in a massive fraud that led to losses of hundreds of millions of dollars for investors. This complaint can be found at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2009/comp20920.pdf. Return to text

- 9. According to the CBEM, examiners should be alert for situations in which top management dominates the board of directors or where top management acts solely at the direction of either the board of directors or a dominant influence on the board of directors. Return to text

- 10. SR Letter 95-51, Rating the Adequacy of Risk Management Processes and Internal Controls at State Member Banks and Bank Holding Companies, states that "boards of directors have the ultimate responsibility for the level of risk taken by their institution. Accordingly, they should approve the overall business strategies and significant policies of their organization, including those related to managing and taking risks, and should also ensure that senior management is fully capable of managing the activities that their institutions conduct." SR Letter 95-51 also states that senior management is responsible for implementing strategies in a manner that limits risks associated with each strategy. Return to text

- 11. SR Letter 03-05 also acknowledges that an institution may place the manager of internal audit under a dual reporting arrangement and states that in such cases, the internal audit manager should report administratively to the CEO and be functionally accountable to the audit committee on issues discovered by the internal audit function. Return to text

- 12. Regulation Y generally regulates the acquisition of control of banks and bank holding companies by companies and individuals, with subpart G applying to appraisal standards. Return to text

- 13. The CBEM defines Matters Requiring Immediate Attention as matters arising from an examination that the Federal Reserve is requiring a banking organization to address immediately. Return to text

- 14. According to SR Letter 06-17, Interagency Policy Statement on the Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses (ALLL), "each institution is responsible for developing, maintaining, and documenting a comprehensive, systematic, and consistently applied process for determining the amounts of the ALLL and the provision for loan and lease losses." Return to text